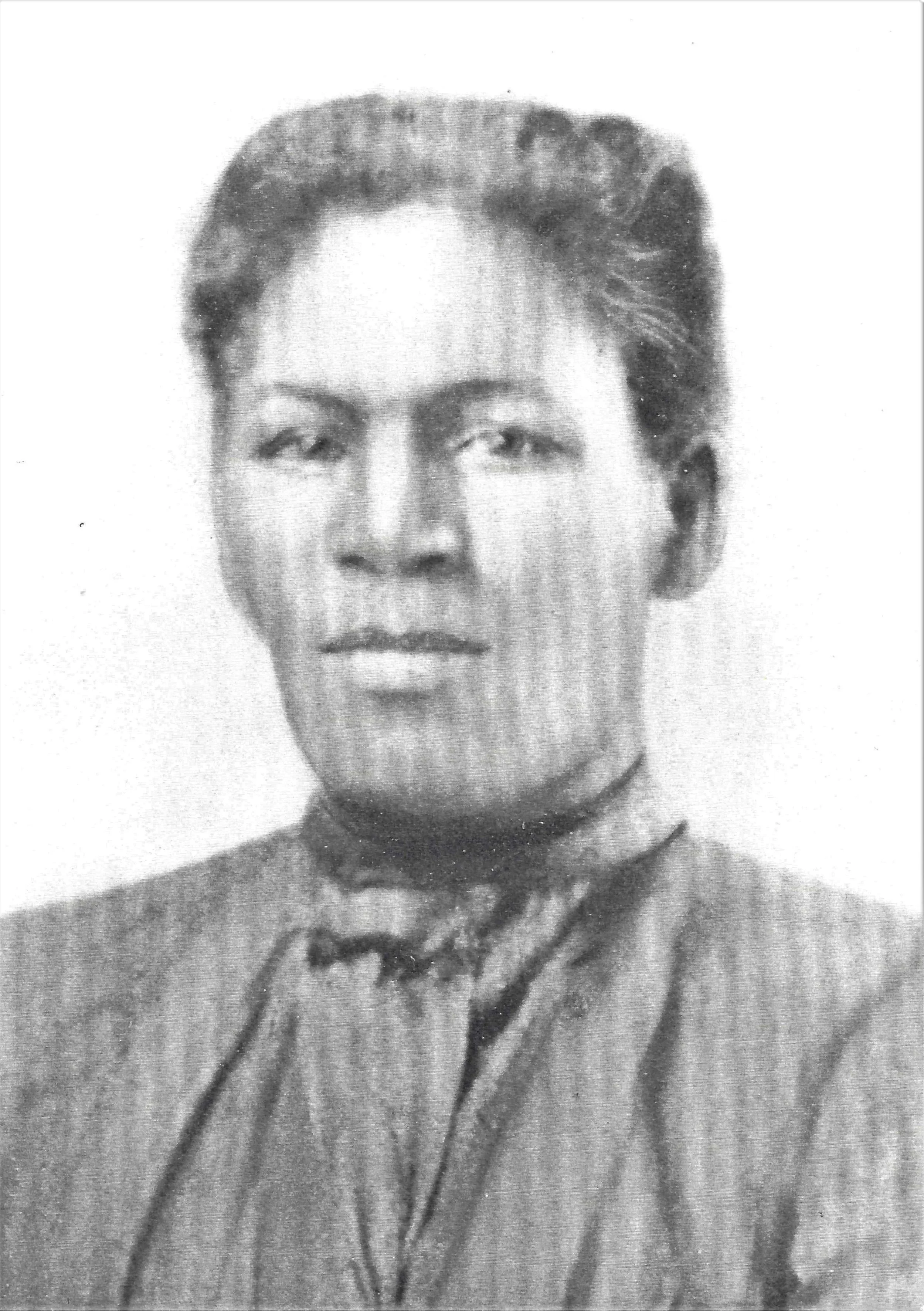

Adaline Wheatley

1847 - 1929

Adaline Wheatley, c 1900

Adaline Wheatley was a resident of the Spocott community her entire life, serving as cook, nurse, house manager, and part-time nanny for the children of John Anthony LeCompte Radcliffe and Sophie Travers Robinson Radcliffe. She married John Columbus Wheatley, a former enslaved worker on the Spocott property, and they raised their seven children at Spocott.

Adaline was born in 1847 to William and Mary Morris,free Blacks who lived on the Spocott property, as did their parents. According to the 1850 Census, she was the fourth child of five. Her older sisters were Mary Ann, Nancy, and Emily; Camiley was two years her junior. Her father was listed as a laborer at Spocott and possibly involved in the Spocott shipbuilding. There is no record of what became of the rest of her family.

In 1847,John AL Radcliffe assumed ownership of the Spocott property and ship building operation. Adaline became a favorite of John and his family. Known early on for her compassion and intelligence, she was revered in the community for her cooking ability and sharp wit. According to the 1870 Census, in 1866, she had a daughter, Mary, but the father is unknown. At that time, John Columbus Wheatley(1845 –1910) returned to Spocott after a term of service in the US Navy. Adaline and Columbus married in 1868 and spent their entire lives at Spocott in the house now preserved on the windmill property.

Adaline and Columbus were given the Spocott tenant house, which at that time was found at the head of the Spocott lane. Columbus worked alongsideJohn on his many construction projects and played a significant role in the farming operation. The family referred to Columbus as a jack-of-all-trades. Adaline continued as the cook throughout her lifetime and gradually assumed additional roles, including nurse and house manager. Thefamily and community affectionately called them“Aunt Adaline” and “Uncle Columbus,” terms of endearment, as both were always considered members of the Radcliffe family.

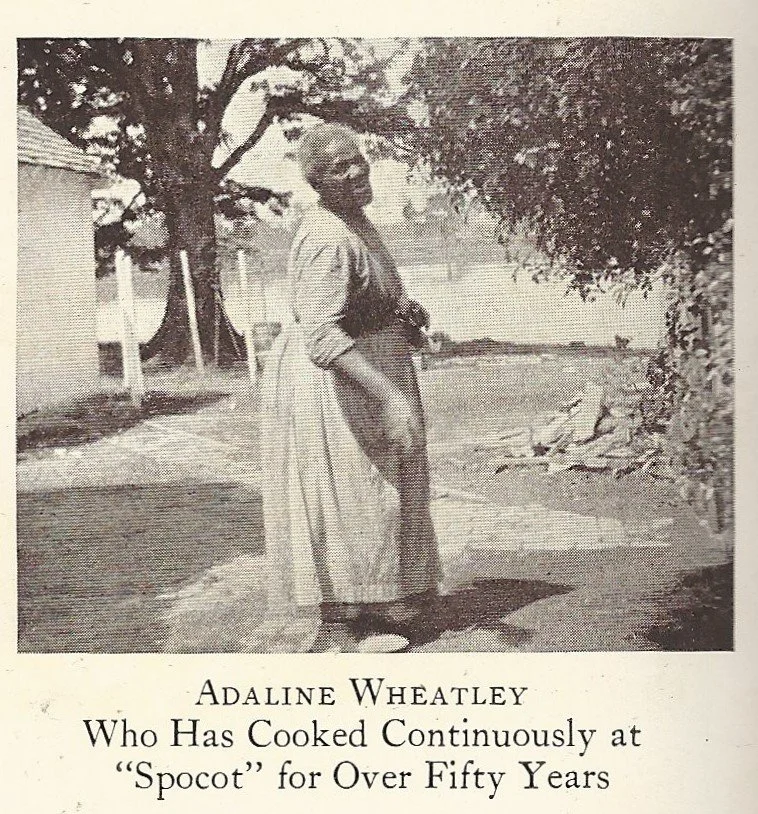

Adaline Wheatley 1928

George L. Radcliffe always spoke of Adaline’s role as chief nurse at Spocott. Although she had no formal nursing training, she possessed enough common sense and basic smarts to fill the shoes. As in the kitchen, she wielded her magic, especially with the children. John and Sophie had both been previously married and had 19 children between the two of them. Spocott was full of children and grandchildren at any point in time. At that time, with so many children on the property, there always seemed to be one in quarantine. Adaline was there to lend her touch. Sophie was in poor health for the last few years, and Adaline became her full-time caregiver. What amazed George was that with all these additional responsibilities, Adaline never missed cooking a meal. John ALRadcliffe died in 1901, and Columbus passed in 1910. Sophie and Adaline lived out their remaining years together at Spocott. Spocott hospitality and prosperity in those years became synonymous with these two strong women.

Adaline was well-versed in many subjects, and all sought out her wisdom. Every visitor spent considerable time in the kitchen, and it was never known whether her cooking or advice was the bigger draw.Her cooking was known far and wide.In1928, she was honored by the Delmarva Eastern Shore Association, which highlighted her on their brochure, referring to her cookery as “witchery in the kitchen.” Swepson Earle, in 1923, included her in his treatise, The ChesapeakeBay Country. All sought her recipes, but surprisingly, she had none. She possessed an instinctive ability to create a fantastic dish, never once referring to a recipe or using a measuring cup or spoon. In her kitchen, one received advice whether solicited it or not, and she would look one right in the eyes as she spoke, never glancing down at whatever cooking preparations she was involved in. Cooking was instinctual for her, and she probably could have prepared an amazing meal in her sleep. But her caring and wisdom endeared her to the family, granting her a place of tremendous respect.

She was always found in the outdoor kitchen at Spocott, between the house and the water. Outdoor kitchens were commonplace at this time, primarily for fire safety. Her coal-fired stove was always red hot, even on hot summer days. Spocott was no ordinary home. In addition to John and Sophie’s large families, there were always cousins and their children and frequent visitors at the house. John had a policy of opening his large house to any visitor anytime. Even at night, the house was overflowing with overnight guests. Sen. George L. Radcliffe recounted one evening when the Governor of Maryland slept on the floor because no bed space was available in the large house. So, Adaline was always cooking for a crowd, often preparing a second dinner when another wave of guests arrived. This may have been why she used no recipes. A planned dinner for 12 could soon turn into a feast for 24.

From Earle, Swepson, The Chesapeake Bay Country, p. 398

Those who watched her cook stood in amazement as she threw ingredients together in a flash, frequently having to increase quantities as the guest list increased, with the result always being a first-class meal. Her reputation spread far and wide. Adaline also had to be the impromptu cook with fish, crabs, oysters, and game suddenly appearing in the kitchen awaiting her magic. She would simply smile and add this to the multiple tasks already ongoing.

Sophie and John added three children of their own in the 1870s, with George, the youngest, born in 1877. Adaline helped raise the children, and George, in later years, often spoke of her as a second mother. He never remembered her being ill herself or taking a day off. Never complaining, she calmly and firmly assisted with everything asked of her. Although George was close to his mother, Adaline's presence and attention made his early years a joy.

Sen. Radcliffe would say that a visitor to Spocott would first greet Sophie and then go out to the kitchen to visit Adaline. There was always something brewing: a meal in progress, a pot of terrapin soup, a pie just out of the oven, or freshly made biscuits. Visitors and family would sit, eat, and converse with Adaline. They would get more than just the latest news or story, although these were welcome; there would be a morsel or two of advice and wisdom intertwined. Sen. Radcliffe remembers one instance when the Maryland Governor sat out in the kitchen for over an hour, sampling her amazing cooking and receiving what he deemed“great” advice on how to run the state as he took several pages of notes. He had been gone so long that the family finally sent out a search party. They should have known where he would be. What a tragedy that those amazing recipes and that marvelous wisdom were never recorded, but they profoundly influenced those who knew her.

Sophie’s health failed during her last five years, and Adaline became her constant companion and caregiver. Both in their 80s, they were inseparable. Even in her advanced years, Adaline continued to cook every meal and manage the house while continuing her round-the-clock nursing care. It was an ironic friendship, considering their very different beginnings. The two spent the better part of their lives together and became inseparable. Sophie passed away on Jan. 17, 1927, and Adaline continued to live at Spocott until her death on June 15, 1929.

The lives and friendships of the Radcliffe and Wheatley families mirrored the changes in the country during the period in which they lived. Born in a time when slavery was still the norm in this area of the country, they evolved with the dissolution of slavery. Sophie came from a family that had accepted slavery, although their enslaved workers had been treated well. Columbus was born into slavery, and Adaline, although free, grew up surrounded by slavery. Freedom brought some choices where one had none before, but there was still a chasm caused by alack of education and opportunity. Adaline’s education was shaped by her experiences. Her children were stunted in their education by the limited education that Blacks received in this area. While in the Maryland Legislature in 1872, John Anthony LeCompte Radcliffe successfully fought for funding for the education of blacks. We know that John and Sophie provided educational experiences for Adaline’s children. Even more significant, her children were given their first work experience on the Spocott property, even when the Radcliffe family fell on hard times in the late 19th century. Adaline’s descendants continued to work at Spocott, some until the early 1970s.

Spocott was extraordinary and unusual at that time because the family had two matriarchs. George L. Radcliffe always credited his two strong female influences in his early years. When Adaline finally passed in 1929, her funeral service was held at a small Black church nearby. She was buried there beside her beloved husband,Columbus. George L. Radcliffe, one of the many children she helped raise, gave the eulogy at her service. Several years later,George paid for a tombstone to go over her grave at Zoar Church Cemetery near Morris Neck. The stone read,“For 65 years devoted employee and friend of Mrs. John A. L. Radcliffe, whose sons Thomas B., J. Sewell, and George L. erect this.” His affection for her was apparent to all. George was to go on and become a United States senator, but he never forgot his roots. Adaline was a remarkable woman. As if we needed further evidence of her impact, her picture was the only one hanging in the Spocott dining room for years after her passing. While we can only speculate about the heights she could have attained in the world today, she was a valuable member of family and community for many years. The most significant testament to Adaline’s influence is that the child she helped raise became a United States senator.